Samuel Pepys

| Samuel Pepys | |

|---|---|

Portrait of Samuel Pepys by J. Hayls. Oil on canvas, 1666, 756 mm × 629 mm National Portrait Gallery, London. |

|

| Born | 23 February 1633 London, England |

| Died | 26 May 1703 (aged 70) Clapham, England |

| Resting place | St Olave's, London, England |

| Nationality | English |

| Education | Huntingdon Grammar School, St Paul's School and Cambridge University |

| Occupation | Naval Administrator started off as Clerk of the Acts working his way up to Chief Secretary to the Admiralty and Tory Member of Parliament for Castle Rising and Harwich |

| Known for | Diary |

| Political party | Tory |

| Board member of | President of the Royal Society, Master of Trinity House, Freeman of the City of London, Freeman of Portsmouth, Treasurer of the Tangier committee |

| Religion | Anglican |

| Spouse | Elisabeth Pepys (née de St Michel) |

| Relatives | Edward Montagu, 1st Earl of Sandwich, Sir Richard Pepys, Lord Chief Justice of Ireland and Richard Edgcumbe, 1st Baron Edgcumbe among others - Cousins of Samuel Pepys |

Samuel Pepys FRS, MP, JP, (pronounced /ˈpiːps/ "peeps") (23 February 1633 – 26 May 1703) was an English naval administrator and Member of Parliament, who is now most famous for his diary. Although Pepys had no maritime experience, he rose by patronage, hard work and his talent for administration, to be the Chief Secretary to the Admiralty under both King Charles II and subsequently King James II. His influence and reforms at the Admiralty were important in the early professionalisation of the Royal Navy.[1]

The detailed private diary he kept during 1660–1669 was first published in the nineteenth century, and is one of the most important primary sources for the English Restoration period. It provides a combination of personal revelation and eyewitness accounts of great events, such as the Great Plague of London, the Second Dutch War and the Great Fire of London.

Contents |

Early life

Pepys was born in Salisbury Court, Fleet Street, London[3][4][5] on 23 February 1633, of John Pepys (1601–1680), a tailor, and Margaret Pepys née Kite (d. 1667), daughter of a Whitechapel butcher.[4] His father's first cousin, Sir Richard Pepys, was elected MP for Sudbury in 1640, and appointed Baron of the Exchequer on 30 May 1654, and Lord Chief Justice of Ireland, on 25 September 1655.

Samuel Pepys was the fifth in a line of eleven children, but child mortality was high and he was soon the eldest.[6] He was baptised at St Bride's Church on 3 March.[4] Pepys did not spend all of his infancy in London, and for a while was sent to live with a nurse, Goody Lawrence, at Kingsland, north of the city.[4] In about 1644 Pepys attended Huntingdon Grammar School, before being educated at St Paul's School, London, circa 1646–1650.[4] He attended the execution of Charles I, in 1649.[4]

In 1650, he went to Cambridge University, having received two exhibitions from St Paul's School (perhaps owing to the influence of Sir George Downing, who was chairman of the judges and for whom he later worked at the exchequer)[7] and a grant from the Mercers Company. On 21 June 1650 he entered his name for Trinity Hall, Cambridge,[8] where his uncle, John Pepys, was a fellow.[4] However, in October he was admitted as a sizar to Magdalene College; he moved there in March 1651 and took his Bachelor of Arts degree in 1654.[9][4] Later that year, or in early 1655, he entered the household of another of his father's cousins, Sir Edward Montagu, who would later be made 1st Earl of Sandwich. He also married the fourteen-year-old Elisabeth de St Michel, a descendant of French Huguenot immigrants, first in a religious ceremony, on 10 October 1655, and later in a civil ceremony, on 1 December 1655, at St Margaret's, Westminster.[10]

Illness

From a young age, Pepys suffered from kidney stones in his urinary tract – a condition from which his mother and brother John also later suffered.[11] He was almost never without pain, as well as other symptoms, including "blood in the urine" (hematuria). By the time of his marriage, the condition was very severe and probably had a serious effect on his ability to engage in sexual intercourse.

In 1657, Pepys took the decision to undertake surgery: this cannot have been an easy option, as the operation was known to be especially painful and hazardous. Nevertheless, Pepys consulted Thomas Hollier, a surgeon; and, on 26 March 1658, the operation took place in a bedroom at the house of Pepys's cousin, Jane Turner.[12] Pepys' stone was successfully removed[13] and he resolved to hold a celebration on every anniversary of the operation, which he did for several years.[14] However, there were long-term effects from the operation: the incision on his bladder broke open again late in his life, and the procedure may have left him sterile – though there is no direct evidence for this, as he was childless before the operation.[15]

In mid-1658 Pepys moved to Axe Yard, near where the modern Downing Street is located. He worked as a teller in the exchequer under George Downing.[4]

The diary

On 1 January 1660, Pepys began to keep a diary. He recorded his daily life for almost ten years. The women he pursued, his friends, his dealings, are all laid out. His diary reveals his jealousies, insecurities, trivial concerns, and his fractious relationship with his wife. It is an important account of London in the 1660s. The juxtaposition of his commentary on politics and national events, alongside the very personal, can be seen from the beginning. His opening paragraphs, written in January 1660, begin:

Blessed be God, at the end of the last year I was in very good health, without any sense of my old pain but upon taking of cold. I lived in Axe yard, having my wife and servant Jane, and no more in family than us three. My wife, after the absence of her terms for seven weeks, gave me hopes of her being with child, but on the last day of the year she hath them again.

The condition of the State was thus. Viz. the Rump, after being disturbed by my Lord Lambert, was lately returned to sit again. The officers of the army all forced to yield. Lawson lie[s] still in the River and Monke is with his army in Scotland. Only my Lord Lambert is not yet come in to the Parliament; nor is it expected that he will, without being forced to it.

–

Diary of Samuel Pepys, January 1660.

The entries from the first few months are filled with news of General George Monck's march on London. In April and May of that year – at this time, he was encountering problems with his wife – he accompanied Montagu's fleet to the Netherlands to bring Charles II back from exile. Montagu was made Earl of Sandwich on 18 June, and the position of Clerk of the Acts to the Navy Board was secured by Pepys on 13 July.[4] As secretary to the board, Pepys was entitled to a £350 annual salary plus the various gratuities and benefits – including bribes – that came with the job: he rejected an offer of £1000 for the position from a rival, and moved to official accommodation in Seething Lane in the City of London soon afterwards.

Public life

On the Navy Board, Pepys proved to be a more able and efficient worker than colleagues in higher positions: a fact that often annoyed Pepys, and provoked much harsh criticism in his diary. Among his colleagues were Admiral Sir William Penn, Sir George Carteret, Sir John Mennes and Sir William Batten.[4]

Learning arithmetic from a private tutor, and using models of ships to make up for his lack of first-hand nautical experience, Pepys came to play a significant role in the board's activities. In September 1660 he was made a Justice of the Peace, and on 15 February 1662 Pepys was admitted as a Younger Brother of Trinity House, and on 30 April he received the freedom of Portsmouth. Through Sandwich, he was involved in the administration of the short-lived English colony at Tangier. He joined the Tangier committee in August 1662 when the colony was first founded, and became its treasurer in 1665. In 1663 he independently negotiated a £3000 contract for Norwegian masts, demonstrating the freedom of action that his superior abilities allowed. He was appointed to a commission of the royal fishery on 8 April 1664.

His job required that he meet with many people to dispense monies and make contracts. He often laments over how he "lost his labour" having gone to some appointment at a coffee house or tavern, there to discover that the person he was seeking was not within. This was a constant frustration to Pepys.

Major events

As well as providing a first-hand account of the Restoration, Pepys's diary is notable for its detailed and unique accounts of several other major events of the 1660s. In particular it is an invaluable source for the study of the Second Anglo-Dutch War of 1665-7, of the Great Plague of 1665, and of the Great Fire of London in 1666. In relation to the Plague and Fire, C.S. Knighton has written: 'From its reporting of these two disasters to the metropolis in which he thrived, Pepys's diary has become a national monument.'[16] Again writing about these events, Robert Latham – the editor of the definitive edition of the diary – has remarked: 'His descriptions of both – agonisingly vivid – achieve their effect by being something more than superlative reporting; they are written with compassion. As always with Pepys it is people, not literary effects, that matter.'[17]

Second Anglo-Dutch War

In early 1665 the start of the Second Anglo-Dutch War placed great pressure on Pepys. With his colleagues being either engaged elsewhere or incompetent, Pepys had to deal with a great deal of business himself. He excelled under the pressure, which was extremely great given the complex and badly funded nature of the Royal Navy.[4] At the outset he proposed a centralised approach to supplying the fleet. His idea was accepted, and he was made surveyor-general of victualling in October 1665. The position brought a further £300 a year.[4]

In 1667, with the war lost, Pepys helped to discharge the navy.[4] The Dutch, who had defeated England on open water, now began to threaten the mainland itself. In June 1667 the Dutch conducted their Raid on the Medway, broke the defensive chain at Gillingham, and towed away the Royal Charles, one of the Royal Navy's most important ships. As with the Fire and the Plague, Pepys again evacuated his wife and his gold from London.[4] While the Dutch raid was a major concern in itself, Pepys was personally placed under a different kind of pressure: the Navy Board, and his role as Clerk of the Acts, came under scrutiny from the public and from parliament. The war ended in August, and on 17 October the House of Commons created a committee of 'miscarriages'.[4] On 20 October, a list of ships and commanders at the time of the division of the fleet in 1666 was demanded from Pepys.[4] However, these demands were actually quite desirable for him: tactical and strategic mistakes were not the responsibility of the Navy Board. The Board did face some allegations regarding the Medway raid, but they were able to exploit the criticism already attracted by the commissioner of Chatham, Peter Pett, to deflect criticism from themselves.[4] The committee accepted this tactic when they reported in February 1668. The Board was, however, criticised for its use of tickets to pay seamen. These tickets could only be exchanged for cash at the Navy's treasury in London.[4] Pepys made a long speech at the bar of the Commons on 5 March 1668 defending this practice. It was, in the words of C.S. Knighton, a 'virtuoso performance'.[4]

The commission was followed by an investigation led by a more powerful authority, the commissioners of accounts. They met at Brooke House, Holborn, and spent two years scrutinising how the war had been financed. In 1669 Pepys had to prepare detailed answers to the committee's eight 'Observations' on the Navy Board's conduct, and in 1670 he was forced to defend his own role. A seaman's ticket with Pepys's name on it was produced as incontrovertible evidence of his corrupt dealings, but thanks to the intervention of the king Pepys emerged from the sustained investigation relatively unscathed.[4]

Great Plague

Outbreaks of plague were not particularly unusual events in London: major epidemics had occurred in 1592, 1603, 1625, and 1636.[18] Furthermore, Pepys was not among the group of people who were most at risk: he did not live in cramped housing, he did not routinely mix with the poor, and he was not required to keep his family in London in the event of a crisis.[19] It was not until June that the unusual seriousness of the plague became apparent, and Pepys's activities in the first five months of the year were not significantly impacted by plague.[20] Indeed, Claire Tomalin writes that 'the most notable fact about Pepys's plague year is that to him it was one of the happiest of his life.' In 1665 he toiled very hard at arduous work, but the outcome was that he quadrupled his fortune.[19] On 31 December, in his annual summary, he wrote that 'I have never lived so merrily (besides that I never got so much) as I have done this plague time'.[21] Nonetheless, it was not the case that Pepys was completely unconcerned by the plague. On 16 August he wrote that:

But, Lord! how sad a sight it is to see the streets empty of people, and very few upon the 'Change. Jealous of every door that one sees shut up, lest it should be the plague; and about us two shops in three, if not more, generally shut up.—Diary of Samuel Pepys, Wednesday, 16 August 1665.

He also chewed tobacco as a protection against infection, and worried that wig-makers might be using the hair of dead people as a raw material. Furthermore, it was Pepys who suggested that the Navy Office should evacuate to Greenwich, although he did offer to remain in town himself. He would later take great pride in his stoicism.[22] Meanwhile, Elisabeth Pepys was sent to Woolwich.[4] She did not return to Seething Lane until January 1666, and was shocked by the sight of St Olave's churchyard, where 300 people had been buried.[23]

Great Fire of London

In the early hours of 2 September 1666, Pepys was woken by his servant who had spotted a fire in the Billingsgate area. He decided the fire was not particularly serious, and returned to bed. Shortly after waking, his servant returned, and reported that 300 houses had been destroyed and that London Bridge was threatened. Pepys went to the Tower to get a better view. Without returning home, he took a boat and observed the fire for over an hour. In his diary, Pepys recorded his observations as follows:

I down to the water-side, and there got a boat and through bridge, and there saw a lamentable fire. Poor Michell's house, as far as the Old Swan, already burned that way, and the fire running further, that in a very little time it got as far as the Steeleyard, while I was there. Everybody endeavouring to remove their goods, and flinging into the river or bringing them into lighters that layoff; poor people staying in their houses as long as till the very fire touched them, and then running into boats, or clambering from one pair of stairs by the water-side to another. And among other things, the poor pigeons, I perceive, were loth to leave their houses, but hovered about the windows and balconys till they were, some of them burned, their wings, and fell down. Having staid, and in an hour's time seen the fire: rage every way, and nobody, to my sight, endeavouring to quench it, but to remove their goods, and leave all to the fire, and having seen it get as far as the Steele-yard, and the wind mighty high and driving it into the City; and every thing, after so long a drought, proving combustible, even the very stones of churches, and among other things the poor steeple by which pretty Mrs.————lives, and whereof my old school-fellow Elborough is parson, taken fire in the very top, an there burned till it fell down—Diary of Samuel Pepys, Sunday, 2 September 1666.

Seeing that the wind was driving the fire westward, he ordered the boat to go to Whitehall, and became the first person to inform the king of the fire. The king told him to go to the Lord Mayor, Thomas Bloodworth and tell him to start pulling houses down. Pepys took a coach back as far as St Paul's Cathedral, before setting off on foot through the burning city. He found the Lord Mayor, who said: "Lord! what can I do? I am spent: people will not obey me. I have been pulling down houses; but the fire overtakes us faster than we can do it." At noon he returned home and 'had an extraordinary good dinner, and as merry, as at this time we could be', before returning to watch the fire in the city once more. Later, he returned to Whitehall, then met his wife in St. James's Park. In the evening they watched the fire from the safety of Bankside: Pepys writes that 'it made me weep to see it'. Returning home, Pepys met his clerk, Tom Hayter, who had lost everything. Hearing news that the fire was advancing, he started to pack up his possessions by moonlight.

A cart arrived at 4am on 3 September, and Pepys spent much of the day arranging the removal of his possessions. Many of his valuables, including his diary, were sent to friend of the Navy Office at Bethnal Green.[24] At night he 'fed upon the remains of yesterday's dinner, having no fire nor dishes, nor any opportunity of dressing any thing.' The next day, Pepys continued to arrange the removal of his possessions. By this point, he believed that Seething Lane was in grave danger, and suggested calling men from Deptford to help pull-down houses and defend the king's property.[24] He described the chaos in the city, and his curious attempt at saving his own goods:

Sir W. Pen and I to Tower-streete, and there met the fire burning three or four doors beyond Mr. Howell's, whose goods, poor man, his trayes, and dishes, shovells, &c., were flung all along Tower-street in the kennels, and people working therewith from one end to the other; the fire coming on in that narrow streete, on both sides, with infinite fury. Sir W. Batten not knowing how to remove his wine, did dig a pit in the garden, and laid it in there; and I took the opportunity of laying all the papers of my office that I could not otherwise dispose of. And in the evening Sir W. Pen and I did dig another, and put our wine in it; and I my Parmazan cheese, as well as my wine and some other things.—Diary of Samuel Pepys, Tuesday, 4 September 1666.

On Wednesday, 5 September, Pepys – who had taken to sleeping on his office floor – was woken by his wife at 2am. She told him that the fire had almost reached All Hallows-by-the-Tower, and that it was at the foot of Seething Lane. He decided to send her and his gold – about £2350 – to Woolwich. In the following days Pepys witnessed looting, disorder and disruption. On 7 September he went to Paul's Wharf and saw the ruins of St Paul's cathedral, of his old school, of his father's house, and of the house in which he had had his stone removed.[25] Despite all this destruction, Pepys's house, office and diary had been saved.

Personal life

The diary gives a detailed account of Pepys's personal life. He liked wine and plays, and the company of other people. He also spent a great deal of time evaluating his fortune and his place in the world. He was always curious and often acted on that curiosity, as he acted upon almost all his impulses. Periodically he would resolve to devote more time to hard work instead of leisure. For example, in his entry for New Year's Eve, 1661, he writes: "I have newly taken a solemn oath about abstaining from plays and wine ...". The following months reveal his lapses to the reader; by 17 February, it is recorded, "Here I drank wine upon necessity, being ill for the want of it."

As well as being one of the most important civil servants of his age, Pepys was a widely cultivated man, taking an interest in books, music, the theatre, and science. He was passionately interested in music; and he composed, sang, and played, for pleasure, and even arranged music lessons for his servants. He played the lute, viol, violin, flageolet, recorder and spinet to varying degrees of proficiency.[4] He was also a keen singer, and performed at home, in coffee houses and even in Westminster Abbey.[4] He and his wife took flageolet lessons from the master Thomas Greeting.[26] He also taught his wife to sing, and paid for dancing lessons for her (although these stopped when he became jealous of the dancing master).

Sexual relations

Propriety did not prevent him from engaging in a number of extramarital liaisons with various women: these were chronicled in his diary, often in some detail, and generally using a cocktail of languages (English, French, Spanish and Latin) when relating the intimate details. The most dramatic of these encounters was with Deborah Willet, a young woman engaged as a companion for Elisabeth Pepys. On 25 October 1668 Pepys was surprised by his wife whilst embracing Deborah Willet: he writes that his wife "coming up suddenly, did find me imbracing the girl con my hand sub su coats; and endeed I was with my main in her cunny. I was at a wonderful loss upon it and the girl also...." Following this event, he was characteristically filled with remorse but (equally characteristically) this did not prevent his continuing to pursue Willet when she had been dismissed from the Pepys household.[27]

The text of the diary

The diary was written in one of the many standard forms of shorthand used in Pepys's time, in this case called Tachygraphy and devised by Thomas Shelton. Though it is clear from its content that it was written as a purely personal record of his life and not for publication, there are indications Pepys actively took steps to preserve the bound manuscripts of his diary. Apart from writing it out in fair copy from rough notes, he also had the loose pages bound into six volumes, catalogued them in his library with all his other books, and must have known that eventually someone would find them interesting.

After the diary

Throughout the period of the diary, Pepys's health suffered from the long hours he worked. Specifically, he believed that his eyesight had been affected by the work he had done.[28] At the end of May 1669, he reluctantly concluded that, for the sake of his eyes, he should completely stop writing and, from then on, only dictate to his clerks[29] which meant he could no longer keep his diary. Pepys and his wife took a holiday to France and the Low Countries in June–October 1669; on their return, Elisabeth fell ill and died on 10 November 1669. Pepys erected a monument to her in the church of St Olave's, Hart Street, in London.

Member of Parliament and Secretary to the Admiralty

In 1672 he became an Elder Brother of Trinity House and in the following year he was promoted to Secretary to the Admiralty Commission and elected Member of Parliament for Castle Rising in Norfolk. In May 1676, he was elected as Master of Trinity House and served in this capacity to 1689.

In 1673 he was involved with the establishment of the Royal Mathematical School at Christ's Hospital, which was to train 40 boys annually in navigation, for the benefit of the Royal Navy and the English merchant navy. In 1675 he was appointed a Governor of Christ's Hospital, and for many years he took a close interest in its affairs. Among his papers are two detailed memoranda on the administration of the school. In 1699 after the successful conclusion of a seven-year campaign to get the master of the Mathematical School replaced by a man who knew more about the sea, he was rewarded for his service as a Governor by being made a Freeman of the City of London.

At the beginning of 1679 Pepys was elected MP for Harwich in Charles II's third parliament which formed part of the Cavalier Parliament. He was elected along with Sir Anthony Deane, a Harwich alderman and leading naval architect, to whom Pepys had been patron since 1662. By May of that year, they were under attack from their political enemies. Pepys resigned as Secretary to the Admiralty, and they were imprisoned in the Tower of London on suspicion of treasonable correspondence with France, specifically leaking naval intelligence. The charges are believed to have been fabricated under the direction of the Anthony Ashley-Cooper, 1st Earl of Shaftesbury.[30] Pepys was accused, among other things, of being a papist. They were released in July, but proceedings against them were not dropped until June 1680.

Though he had resigned from the Tangier committee in 1679, in 1683 he was sent to Tangier to assist Lord Dartmouth with the evacuation and abandonment of the English colony. After six months' service, he travelled back through Spain accompanied by the Naval engineer Edmund Dummer, returning to England after a particularly rough passage on 30 March 1684.[31] In June 1684, once more in favour, he was appointed King's Secretary for the affairs of the Admiralty, a post that he retained after the death of Charles II (February 1685) and the accession of James II. The phantom Pepys Island, alleged to be near South Georgia, was named after him in 1684, having been first discovered during his tenure at the Admiralty.

From 1685 to 1688, he was active not only as Secretary for the Admiralty, but also as MP for Harwich. He had been elected MP for Sandwich, but was contested and immediately withdrew to Harwich. When James fled the country at the end of 1688, Pepys's career also came to an end. In January 1689, he was defeated in the parliamentary election at Harwich; in February, one week after the accession of William and Mary, he resigned his secretaryship.

Royal Society

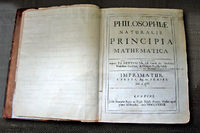

He was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society in 1665 and served as its President from 1 December 1684 to 30 November 1686. Isaac Newton's Principia Mathematica was published during this period and its title-page bears Pepys' name. There is a probability problem, called the "Newton–Pepys problem", that arose out of correspondence between Newton and Pepys about whether one is more likely to roll at least one six with six dice or at least two sixes with twelve dice.[32] It has been only recently noted that while the gambling advice Newton gave Pepys was correct, the logical argument Newton included with it was unsound.[33]

Retirement

From May to July 1689, and again in June 1690, he was imprisoned on suspicion of Jacobitism, but no charges were ever successfully brought against him. After his release, he retired from public life, aged 57. Ten years later, in 1701, he moved out of London, to a house at Clapham owned by his friend William Hewer, known as 'Will', who had begun his career working for Pepys in the admiralty.[34] Clapham was then in the country though now very much part of Greater London, and Pepys lived there until his death, on 26 May 1703. He had no children and bequeathed his estate to his nephew, John Jackson.[35] His former protege and friend Hewer acted as the executor.[36]

Pepys Library

Pepys was a lifelong bibliophile and carefully nurtured his large collection of books, manuscripts, and prints. At his death, there were more than 3,000 volumes, including the diary, all carefully catalogued and indexed; they form one of the most important surviving 17th century private libraries. The most important items in the Library are the six original bound manuscripts of Pepys's diary but there are other remarkable holdings, including:[37]

- Incunabula by William Caxton, Wynkyn de Worde and Richard Pynson

- Sixty medieval manuscripts

- The Pepys Manuscript: a late fifteenth-century English choirbook

- Naval records such as two of the 'Anthony Rolls', illustrating the Royal Navy's ships circa 1546, including the Mary Rose

- Sir Francis Drake's personal almanac

- Over 1,800 printed ballads: one of the finest collections in existence.[38]

Pepys made detailed provisions in his will for the preservation of his book collection; and, when his nephew and heir, John Jackson, died, in 1723, it was transferred, intact, to Magdalene College, Cambridge, where it can be seen in the Pepys Building. The bequest included all the original book cases and his elaborate instructions that placement of the books "...be strictly reviewed and, where found requiring it, more nicely adjusted".

Publication history of the diary

The Reverend John Smith was engaged to transcribe the diaries into plain English; and he laboured at this task for three years, from 1819 to 1822, unaware that a key to the shorthand system was stored in Pepys's library a few shelves above the diary volumes. Smith's transcription—which is also kept in the Pepys Library – was the basis for the first published edition of the diary, released in two volumes in 1825.

A second transcription, done with the benefit of the key, but often less accurately, was completed in 1875 by Mynors Bright, and published in 1875–1879.[39] Henry B. Wheatley, drawing on both his predecessors, produced a new edition in 1893[40]–1899, revised in 1926, with extensive notes and an index.

The complete and definitive edition, edited and transcribed by Robert Latham and William Matthews, was published by Bell & Hyman, London, and the University of California Press, Berkeley, in nine volumes, along with separate Companion and Index volumes, over the years 1970–1983. Various single-volume abridgements of this text are also available.

The Introduction in volume I provides a scholarly but readable account of "The Diarist", "The Diary" ("The Manuscript", "The Shorthand", and "The Text"), "History of Previous Editions", "The Diary as Literature", and "The Diary as History". The Companion provides a long series of detailed essays about Pepys and his world.

Biographical studies

Several detailed studies of Pepys' life are available. Arthur Bryant published his three-volume study in 1933–1938, long before the definitive edition of the diary, but, thanks to Bryant's lively style, it is still of interest. In 1974 Richard Ollard produced a new biography that drew on Latham's and Matthew's work on the text, and benefited from the author's deep knowledge of Restoration politics. The most recent general study is by Claire Tomalin, which won the 2002 Whitbread Book of the Year award, the judges calling it a "rich, thoughtful and deeply satisfying" account that unearths "a wealth of material about the uncharted life of Samuel Pepys". On 1 January 2003 Phil Gyford started a weblog, pepysdiary.com, that serialised the diary one day each evening together with annotations from public and experts alike (some had earlier access). In December 2003 the blog won the best specialist blog award in The Guardian's Best of British Blogs.[41]

Notes

- ↑ Ollard, 1984, ch.16

- ↑ National Portrait Gallery website: Elizabeth (sic) Pepys

- ↑ Tomalin (2002), p3. "He was born in London, above the shop, just off Fleet Street, in Salisbury Court."

- ↑ 4.00 4.01 4.02 4.03 4.04 4.05 4.06 4.07 4.08 4.09 4.10 4.11 4.12 4.13 4.14 4.15 4.16 4.17 4.18 4.19 4.20 4.21 4.22 4.23 Knighton (2004)

- ↑ Wheatley Particulars of the life of Samuel Pepys: "but the place of birth is not known with certainty. Samuel Knight, ... (having married Hannah Pepys, daughter of Talbot Pepys of Impington), says positively that it was at Brampton"

- ↑ Trease 1972, p.6

- ↑ 'Samuel Pepys - The Unequalled Self', Claire Tomalin, p.28

- ↑ Pepys, Samuel in Venn, J. & J. A., Alumni Cantabrigienses, Cambridge University Press, 10 vols, 1922–1958.

- ↑ Trease 1972, p.13, 17

- ↑ Knighton (2004). This was because religious ceremonies were not legally recognised during the Interregnum. The couple regularly celebrated the anniversary of the former date

- ↑ Trease 1972, p.16

- ↑ The procedure, described by Pepys as being "cut of the stone", was conducted without the use of anaesthetics or antiseptics, and involved restraining the patient with ropes and four strong men; the surgeon then made an incision along the perineum (between the scrotum and the anus), about three inches (8 cm) long and deep enough to cut into the bladder. The stone was removed through this opening with pincers from below, assisted, from above, by a tool inserted into the bladder through the penis. A detailed description can be found in Tomalin (2002)

- ↑ The stone was described as being the size of a tennis ball. Presumably a real tennis ball, which is slightly smaller than a modern lawn tennis ball, but still an unusually large stone

- ↑ On Monday 26 March 1660, he wrote, in his diary, "This day it is two years since it pleased God that I was cut of the stone at Mrs. Turner's in Salisbury Court. And did resolve while I live to keep it a festival, as I did the last year at my house, and for ever to have Mrs. Turner and her company with me."

- ↑ There are references in the Diary to pains in his bladder, whenever he caught cold. In April 1700, Pepys wrote, to his nephew Jackson, "It has been my calamity for much the greatest part of this time to have been kept bedrid, under an evil so rarely known as to have had it matter of universal surprise and with little less general opinion of its dangerousness; namely, that the cicatrice of a wound occasioned upon my cutting of the stone, without hearing anything of it in all this time, should after more than 40 years' perfect cure, break out again." After Pepys' death, the post-mortem examination showed his left kidney was completely ulcerated; seven stones, weighing four and a half ounces (130 g), also were found. His bladder was gangrenous, and the old wound was broken open again

- ↑ Knighton (2004).

- ↑ "Short biography [of Pepys"]. Pepys Library website. http://www.magd.cam.ac.uk/pepys/latham.html.

- ↑ Tomalin (2004), p. 167

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Tomalin (2004), p. 168

- ↑ Tomalin (2004), p. 168

- ↑

Diary of Samuel Pepys, Sunday, 31 December 1665.

Diary of Samuel Pepys, Sunday, 31 December 1665. - ↑ Tomalin (2004), pp. 174-5

- ↑ Tomalin (2004), pp. 177-8

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 Tomalin (2004), p. 230

- ↑ Tomalin (2004), p. 232

- ↑ Biography of Thomas Greeting The Pleasant Companion-The Flageolets Site

- ↑ Mystery of Pepys' affair solved BBC News 24 14 October 2006

- ↑ In Latham and Matthews's Companion to the diary, Martin Howard Stein suggests that Pepys suffered from a combination of astigmatism and long sight.

- ↑ One of his clerks was Paul Lorrain who became well known as Ordinary of Newgate Prison

- ↑ Wheatley "Shaftesbury and the others not having succeeded in getting at Pepys through his clerk, soon afterwards attacked him more directly, using the infamous evidence of Colonel Scott"

- ↑ Fox, Celina (2007). "The Ingenious Mr Dummer: Rationalizing the Royal Navy in Late Seventeenth-Century England" (PDF). Electronic British Library Journal. p. 22. http://www.bl.uk/eblj/2007articles/pdf/ebljarticle102007.pdf. Retrieved 2 October 2009.

- ↑ Eric W. Weisstein. "Newton-Pepys Problem". Wolfram MathWorld. http://mathworld.wolfram.com/Newton-PepysProblem.html. Retrieved 2008-06-28.

- ↑ S. M. Stigler, 'Isaac Newton as Probabilist,' Statistical Science, Vol. 21 (2006), pp.400-403

- ↑ footnote on Will Hewer, The Diary of Samuel Pepys, Vol. 10, Samuel Pepys, Robert Latham, William Matthews, University of California Press, 2001

- ↑ Pepys disinherited his nephew Samuel Jackson for marrying contrary to his wishes. Instead Pepys settled his estate on nephew John Jackson, who was unmarried at the time of Pepys's death in 1703. When John Jackson died in 1724, his estate reverted to Jackson's wife Anne, daughter of Archdeacon Samuel Edgeley [1], niece of Will Hewer and sister of Hewer Edgeley, nephew and godson of Pepys' old employee and friend Will Hewer. Meanwhile, the childless Will Hewer left his immense estate – consisting mostly of the Clapham property, as well as lands in Clapham, London, Westminster and Norfolk – to his nephew Hewer Edgeley, on the condition that the nephew (and godson) would adopt the surname Hewer. So Will Hewer's heir became Hewer Edgeley-Hewer, and he adopted the old Will Hewer home in Clapham as his residence. Thus did members of the Edgeley family come to acquire the estates of both Samuel Pepys and of his former employee at the Admiralty Will Hewer: sister Anne inheriting Pepys' estate; brother Hewer inheriting that of Pepys' friend Hewer. On the death of Hewer Edgeley-Hewer in 1728, the old Hewer estate went to Edgeley-Hewer's widow Elizabeth, who left the 432-acre (1.75 km2) estate to Levett Blackborne, Esq., the son of Abraham Blackborne, merchant of Clapham, and other family members, who later sold it off in lots. Lincoln's Inn barrister Levett Blackborne also later acted as attorney in legal scuffles for the heirs who had inherited the Peyps estate

- ↑ Will Hewer, The Diary of Samuel Pepys, Samuel Pepys, 1899. http://books.google.com/books?id=Gyq6euwfZj8C&pg=RA2-PA271&lpg=RA2-PA271&dq=%22hewer+edgeley&source=web&ots=o72b50H_ea&sig=W4uwNTXgZ-Icye0kfgkPO5yTTv0&hl=en#PRA2-PA271,M1.

- ↑ Pepys Library website

- ↑ English Broadside Ballad Archive

- ↑ "Samuel Pepys Diary". http://www.pepys.info.

- ↑ Wheatley

- ↑ "The best of British blogging". The Guardian. 2003-12-18. Archived from the original on 2007-02-08. http://web.archive.org/web/20070208185322rn_1/technology.guardian.co.uk/online/weblogs/story/0,14024,1108883,00.html. "prize went to Phil Gyford's remarkable Pepys' Diary."

See also

- Rota Club

References

- Bryant, Arthur (1933). Samuel Pepys (I: The man in the making. II: The years of peril. III: The saviour of the navy) (Revised 1948. Reprinted 1934, 1961, etc. ed.). Cambridge: University Press. LCC DA447.P4 B8.

- Ollard, Richard (1984). Pepys: a biography (First published 1974 ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-281466-4.

- Tomalin, Claire (2002). Samuel Pepys: the unequalled self. London: Viking. ISBN 0-670-88568-1.

- Trease, Geoffrey (1972). Samuel Pepys and his world. Norwich, Great Britain: Jorrold and Son.

- Andrew Godsell "Samuel Pepys: A Man and His Diary" in "Legends of British History" 2008

- C. S. Knighton, ‘Pepys, Samuel (1633–1703)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, (Oxford University Press, 2004).

Editions of letters and other publications by Pepys

- Henry B. Wheatley, ed (1893). The Diary of Samuel Pepys M.A. F.R.S.. London: George Bell & Sons.

- Pepys, Samuel (1995) Robert Latham ed. Samuel Pepys and the Second Dutch War. Pepys's Navy White Book and Brooke House Papers Aldershot: Scholar Press for the Navy Records Society [Publications, Vol 133] ISBN 1-85928-136-2

- Pepys, Samuel (2004). C. S. Knighton. ed. Pepys's later diaries. Stroud: Sutton. ISBN 0-7509-3656-8.

- Pepys, Samuel (2005). Guy de la Bedoyere. ed. Particular friends: the correspondence of Samuel Pepys and John Evelyn (2nd edition ed.). Woodbridge: Boydell & Brewer. ISBN 1-84383-134-1.

- Pepys, Samuel (2006). Guy de la Bedoyere. ed. The letters of Samuel Pepys, 1656-1703. Woodbridge: Boydell. ISBN 1-84383-197-X.

- Seal, Jeremy (2003). "The Wreck Detectives: Stirling Castle". Channel 4. http://www.channel4.com/science/microsites/W/wreck_detectives_2003/the_wrecks/the_stirling_castle/history.html. Retrieved 2006-06-06. – Some historical background on Pepys and the Royal Navy.

Further reading

The Diary.

- Volume I. Introduction and 1660. ISBN 0-7135-1551-1

- Volume II. 1661. ISBN 0-7135-1552-X

- Volume III. 1662. ISBN 0-7135-1553-8

- Volume IV. 1663. ISBN 0-7135-1554-6

- Volume V. 1664. ISBN 0-7135-1555-4

- Volume VI. 1665. ISBN 0-7135-1556-2

- Volume VII. 1666. ISBN 0-7135-1557-0

- Volume VIII. 1667. ISBN 0-7135-1558-9

- Volume IX. 1668–9. ISBN 0-7135-1559-7

- Volume X. Companion. ISBN 0-7135-1993-2

- Volume XI. Index. ISBN 0-7135-1994-0

- C. S. Knighton Pepys and the Navy (Stroud: Sutton Publishing, 2003).

- N. A. M. Rodger, The Command of the Ocean: A Naval History of Britain, 1649-1815 (London: 2004 / New York: 2005). Includes an extensive specialist annotated bibliography.

External links

Some of the older editions of the diary are available online:

There are also two encyclopedic sites about Pepys based on these free editions:

- Phil Gyford's Samuel Pepys' diary, which provides a daily entry from the diary, as well as detailed background articles, plus annotations from readers.

- Duncan Grey's pages on Pepys

And other Pepys sites:

- Pepys library online at Magdalene College, Cambridge, including an essay by Robert Latham

- Pepys Ballad Archive

- The Samuel Pepys Club

- Pepys, Visits

| Parliament of England | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Sir Robert Paston Sir John Trevor |

Member for Castle Rising 1673–1679 With: Sir John Trevor |

Succeeded by Sir Robert Howard Sir John Trevor |

| Preceded by Sir Capel Luckyn Thomas King (MP) |

Member for Harwich 1679 With: Anthony Deane |

Succeeded by Sir Thomas Middleton Sir Philip Parker, Bt |

| Preceded by Sir Thomas Middleton Sir Philip Parker, Bt |

Member for Harwich 1685–1689 With: Anthony Deane |

Succeeded by John Eldred Sir Thomas Middleton |

|

||||||||